The Shrewsbury hoard is one of the largest coin hoards ever found in Shropshire. It’s excavation, conservation and detailed study has revealed the secrets of a Roman time capsule which had lain hidden for almost 1700 years.

The Discovery:

As often happens the first we at the PAS know of a significant find is when the phone rings. It doesn’t often happen that someone says: “hello, I’ve just started metal detecting. I think you might be interested in my first find – it looks like a big jar of coins”. Nothing prepared me for the photo that was sent through of a Roman storage jar overflowing with coins:

The hoard of Roman coins was found in August 2009 by Nic Davis who had recently taken up the hobby of metal detecting. Nic was detecting a modern bridleway in a tree plantation near Shrewsbury. Unfortunately, he was unaware that he needed to gain permission from the landowner before he began metal detecting, even on a public right of way. All land, whether road verge, bridle or foot path is owned and managed by someone and so it is key to gain permission from that person before metal detecting or fieldwalking. On discovering the hoard Nic dug the pot up and took it home, and then started to work out what to do next. Luckily he thought the local museum would be interested and so picked up the phone and talked to me.

Nic and I arranged a meeting face where we went to the findspot and also looked at the coins in more detail. We identified the landowner and started negotiations to arrange a proper archaeological excavation. We also contacted the coroner to inform him of the find.

It was obvious that this was a well preserved Roman vessel and from its weight was full of coins. It was also apparent that the surrounding archaeology had been undisturbed by agriculture. The hoard itself was in remarkable condition. The jar was broken at the neck but well preserved below. The coins on the top were loose, but those in the pot were fused as one solid mass.

It is essential for all metal detector users to be familiar with the code of conduct for responsible metal detecting: http://finds.org.uk/getinvolved/guides/codeofpractice

Peter Reavill and Hugh Hannaford Exavating Coin Hoard

Hugh Hannaford Exavating Coin Hoard

The Excavation:

We were very lucky, and grateful, that Shropshire Council joint funded the excavation with the PAS. Hugh Hannaford, an experienced council archaeologist was available to help and a local metal detectorist, Trevor Brown, also volunteered.

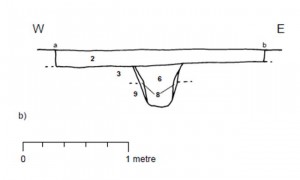

We excavated a small trench (2m x 2m) over the point where Nic had found the pot and revealed that he had caused minimum disturbance to archaeological deposits at the site other than the removal of the hoard itself. We identified a large flat stone, which was originally discovered by the finder during his excavation. We think that this acted as a marker to enable the original owner to return to where they had buried the pot. The depth of the pit would suggest that the neck of the vessel was relatively close to the original ground surface and it is possible that the stone covered the neck of the vessel and therefore acted as a lid as well.

The presence of Trevor and his skill with a detector was needed; with his help recovered nearly 300 coins from the excavation.

The archaeological sequence suggests that the hoard was inserted into a pre-prepared hole in the ground, and topped up with coins piecemeal over time.

All the coins from the hoard were removed and the area around the findspot was checked in case of further archaeological deposits (other coins or hoard).

Once the excavation had taken place the hoard was transported to the British Museum for more detailed work.

Site after excavation

Finished excavation

Section drawing of hole pot was found in

Conservation and Cataloguing:

Conservation in action

Before the hoard could even be looked at by the specialists in the Department of Coins and Medals it needed considerable conservation work. This was funded by grants from the Roman Research Trust and the Haverfield Trust. The majority of the work on the hoard was undertaken by Ellen Van Bork, Pippa Pearce and colleagues in the Conservation Department of the British Museum.

In total there were a staggering 9315 coins within the hoard

The coins were removed from the pot in eight layers of approximately 1000 coins in order to assess the presence of any internal stratigraphy. During this work, some fragments of textile were found within the pot, well-preserved by their proximity to the copper coins. The coins were then cleaned to enable a detailed study to be undertaken. This expert study was led by Dr Eleanor Ghey.

Eleanor Ghey at work

Eleanor found that the coins contained in the vessel and in the soil immediately around it are all of types that were likely to have been in circulation at the time of burial. The latest coins in the hoard can be dated to AD 333-335. However the hoard contained coins in varying numbers dating from the period 313-335 AD. There were also a few earlier ‘radiate’ coins (18) that dated 260-293 AD.

The internal stratigraphy of the pot suggests that the latest coins were added in a later deposition event, as they are only significantly present in the upper three layers and the scattered coins outside the pot. This is hugely significant and could shed light on the nature of hoards in general. This is especially true as the vast majority of Roman coin hoards have been spread by the plough and so can not be interrogated as forensically as this example.

Textiles attached to coins

The lower phases of the pot also contained several fragments of preserved cloth and an iron nail. This is a rare survival, as organic remains normally rot in the ground. The cloth has been preserved here by the copper in the coins which has stopped bacterial action that destroys organic matter. The presence of these materials is intriguing and could hint at the presence of a cloth bag deposited within the hoard. One interpretation is that this bag may have been closed with a nail, although this is highly speculative. This practice, although rare, is possible evidence of a ritual offering. In the Roman world gifts were given to the gods in anticipation of future results (such as recovery of stolen property, improved health or a good harvest).

Inquest

An inquest into the hoard was held today (25th October) by Mr John Ellery, HM Coroner for North and Mid Shropshire. At this inquest he declared the find treasure as it fulfilled the conditions laid out by the Treasure Act being:

- The find was more than 300 years old

- The coins were all from the same findspot

- And that there were more than 10 coins of less than 10% precious metal

What was the hoard worth in Roman times

Reverse Types of the Coins from the Shrewsbury Hoard

The majority of the coins are known as nummi (which just means coin). These are made of bronze (copper alloy) and have small variable traces of silver within them. Nummi are one of the most commonly found coins in Roman Britain. Estimates as to their buying power vary. It is thought that each nummus probably had a value broadly equivalent to that of our modern £1 coin. Thus the coins are likely to represent less than one year’s pay for a Roman legionary soldier. The sheer number of coins, however, still represents considerable material wealth. This could be either that of an individual or of a community.

What is the Significance of the Shrewsbury Hoard

Dr Eleanor Ghey (British Museum) “This is an exceptional find of late Roman coins from Shropshire. It challenges the view that the wealth circulating in the south of Britain at this time had little impact on the areas further north and west. Some of the coins in the hoard were produced in the eastern Mediterranean and travelled a long distance in the short time before they were buried. The fact that the coins were still in their pot when it was excavated has given us a fascinating snapshot of Roman life. Whoever buried these coins kept their location secret for a number of years before adding more to the hoard”.

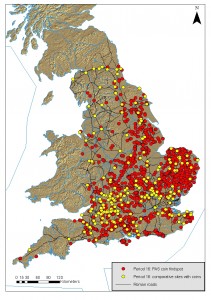

Locally: This is a significant group of coins and suggests some form of significant material wealth amongst the local populace. The archaeology of Shropshire is rich in Roman heritage but very little is known about the later periods. Generally it is thought that the early 4th century was a time of plenty with many of the troubles of the previous 50 years settled. In Shropshire though the later 4th century is poorly represented in excavated villas and large farmsteads as well as finds reported through the PAS. This is supported by the map of Roman coin loss reported through the PAS looking at coins made between 317-330 AD (created by Philippa Walton). This map shows the bias towards the South and East during this period.

PAS findspots of coins dated 317-330

Nationally: This hoard has given a unique opportunity to study a stratified deposit sealed within a pot. It is likely to give specialists further insight into other coin hoards without internal straigraphy which will add to our knowledge of the Romans.

What happens next and where will it go:

The hoard will be valued by Treasure Valuation Committee in London who will advise on the reward payable to finder and landowner.

Once a reward has been fixed, Shropshire Museums hope to raise funds to acquire the hoard for display within the county.

Peter will be speaking about recent PAS finds from Shropshire – including this important hoard – at an Archaeological Dayschool in Shrewsbury, Shropshire on 12th November 2011.