Total posts:

187

11/09/2011

Roman denarii are fairly common finds in Lincolnshire, as are Roman finger rings, but to get a coin reworked as a setting is rather special. Take a look at LIN-A8E677.

A silver denarius of Julia Maesa reworked into a circular bezel for a finger ring; Treasure reference number 2011 T752. The edge of the coin has been raised up from the reverse to form a neat collar. The ‘head’ side of the coin depicting the draped bust of Julia Maesa has been used as the base of the bezel whereas the ‘reverse’ side of the coin has been used for display. The reverse depicts Felicitas standing left, sacrificing over altar and holding long caduceus, star in right field.

The coin is as follows:

Obverse: Draped bust right, IV[LI]A [MAESA AVG]

Reverse: Felicitas standing left, sacrificing over altar and holding long caduceus, star in right field, [SAECVLI FE]LICI[TAS]

Mint of Rome, AD 220-22. Ref: RIC 271.

Catherine Johns comments in The Jewellery of Roman Britain 1996, p.58, on jewellery set with coins, that ‘To all intents and purposes the custom applies only to gold jewellery set with gold coins, and it appears to have been far more popular on the Continent than in Britain’. Only one other similar coin-bezel is recorded on the Portable Antiquities Scheme database, which is an example from Chirton, Wiltshire (WILT-B0C652) that reuses a silver denarius of Plautilla, wife of Caracalla. The reverse of this coin depicts Concordia holding a patera and sceptre, though unlike the Ulceby example the Chirton bezel uses the bust of Caracalla as the display side.

10/25/2011

The Shrewsbury hoard is one of the largest coin hoards ever found in Shropshire. It’s excavation, conservation and detailed study has revealed the secrets of a Roman time capsule which had lain hidden for almost 1700 years.

The Discovery:

As often happens the first we at the PAS know of a significant find is when the phone rings. It doesn’t often happen that someone says: “hello, I’ve just started metal detecting. I think you might be interested in my first find – it looks like a big jar of coins”. Nothing prepared me for the photo that was sent through of a Roman storage jar overflowing with coins:

The hoard of Roman coins was found in August 2009 by Nic Davis who had recently taken up the hobby of metal detecting. Nic was detecting a modern bridleway in a tree plantation near Shrewsbury. Unfortunately, he was unaware that he needed to gain permission from the landowner before he began metal detecting, even on a public right of way. All land, whether road verge, bridle or foot path is owned and managed by someone and so it is key to gain permission from that person before metal detecting or fieldwalking. On discovering the hoard Nic dug the pot up and took it home, and then started to work out what to do next. Luckily he thought the local museum would be interested and so picked up the phone and talked to me.

Nic and I arranged a meeting face where we went to the findspot and also looked at the coins in more detail. We identified the landowner and started negotiations to arrange a proper archaeological excavation. We also contacted the coroner to inform him of the find.

It was obvious that this was a well preserved Roman vessel and from its weight was full of coins. It was also apparent that the surrounding archaeology had been undisturbed by agriculture. The hoard itself was in remarkable condition. The jar was broken at the neck but well preserved below. The coins on the top were loose, but those in the pot were fused as one solid mass.

It is essential for all metal detector users to be familiar with the code of conduct for responsible metal detecting: http://finds.org.uk/getinvolved/guides/codeofpractice

Peter Reavill and Hugh Hannaford Exavating Coin Hoard

Hugh Hannaford Exavating Coin Hoard

The Excavation:

We were very lucky, and grateful, that Shropshire Council joint funded the excavation with the PAS. Hugh Hannaford, an experienced council archaeologist was available to help and a local metal detectorist, Trevor Brown, also volunteered.

We excavated a small trench (2m x 2m) over the point where Nic had found the pot and revealed that he had caused minimum disturbance to archaeological deposits at the site other than the removal of the hoard itself. We identified a large flat stone, which was originally discovered by the finder during his excavation. We think that this acted as a marker to enable the original owner to return to where they had buried the pot. The depth of the pit would suggest that the neck of the vessel was relatively close to the original ground surface and it is possible that the stone covered the neck of the vessel and therefore acted as a lid as well.

The presence of Trevor and his skill with a detector was needed; with his help recovered nearly 300 coins from the excavation.

The archaeological sequence suggests that the hoard was inserted into a pre-prepared hole in the ground, and topped up with coins piecemeal over time.

All the coins from the hoard were removed and the area around the findspot was checked in case of further archaeological deposits (other coins or hoard).

Once the excavation had taken place the hoard was transported to the British Museum for more detailed work.

Site after excavation

Finished excavation

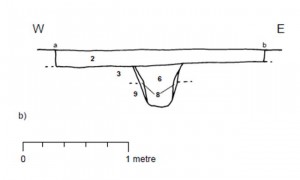

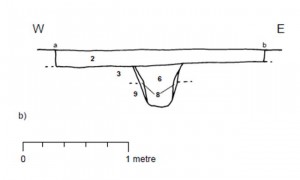

Section drawing of hole pot was found in

Conservation and Cataloguing:

Conservation in action

Before the hoard could even be looked at by the specialists in the Department of Coins and Medals it needed considerable conservation work. This was funded by grants from the Roman Research Trust and the Haverfield Trust. The majority of the work on the hoard was undertaken by Ellen Van Bork, Pippa Pearce and colleagues in the Conservation Department of the British Museum.

In total there were a staggering 9315 coins within the hoard

The coins were removed from the pot in eight layers of approximately 1000 coins in order to assess the presence of any internal stratigraphy. During this work, some fragments of textile were found within the pot, well-preserved by their proximity to the copper coins. The coins were then cleaned to enable a detailed study to be undertaken. This expert study was led by Dr Eleanor Ghey.

Eleanor Ghey at work

Eleanor found that the coins contained in the vessel and in the soil immediately around it are all of types that were likely to have been in circulation at the time of burial. The latest coins in the hoard can be dated to AD 333-335. However the hoard contained coins in varying numbers dating from the period 313-335 AD. There were also a few earlier ‘radiate’ coins (18) that dated 260-293 AD.

The internal stratigraphy of the pot suggests that the latest coins were added in a later deposition event, as they are only significantly present in the upper three layers and the scattered coins outside the pot. This is hugely significant and could shed light on the nature of hoards in general. This is especially true as the vast majority of Roman coin hoards have been spread by the plough and so can not be interrogated as forensically as this example.

Textiles attached to coins

The lower phases of the pot also contained several fragments of preserved cloth and an iron nail. This is a rare survival, as organic remains normally rot in the ground. The cloth has been preserved here by the copper in the coins which has stopped bacterial action that destroys organic matter. The presence of these materials is intriguing and could hint at the presence of a cloth bag deposited within the hoard. One interpretation is that this bag may have been closed with a nail, although this is highly speculative. This practice, although rare, is possible evidence of a ritual offering. In the Roman world gifts were given to the gods in anticipation of future results (such as recovery of stolen property, improved health or a good harvest).

Inquest

An inquest into the hoard was held today (25th October) by Mr John Ellery, HM Coroner for North and Mid Shropshire. At this inquest he declared the find treasure as it fulfilled the conditions laid out by the Treasure Act being:

- The find was more than 300 years old

- The coins were all from the same findspot

- And that there were more than 10 coins of less than 10% precious metal

What was the hoard worth in Roman times

Reverse Types of the Coins from the Shrewsbury Hoard

The majority of the coins are known as nummi (which just means coin). These are made of bronze (copper alloy) and have small variable traces of silver within them. Nummi are one of the most commonly found coins in Roman Britain. Estimates as to their buying power vary. It is thought that each nummus probably had a value broadly equivalent to that of our modern £1 coin. Thus the coins are likely to represent less than one year’s pay for a Roman legionary soldier. The sheer number of coins, however, still represents considerable material wealth. This could be either that of an individual or of a community.

What is the Significance of the Shrewsbury Hoard

Dr Eleanor Ghey (British Museum) “This is an exceptional find of late Roman coins from Shropshire. It challenges the view that the wealth circulating in the south of Britain at this time had little impact on the areas further north and west. Some of the coins in the hoard were produced in the eastern Mediterranean and travelled a long distance in the short time before they were buried. The fact that the coins were still in their pot when it was excavated has given us a fascinating snapshot of Roman life. Whoever buried these coins kept their location secret for a number of years before adding more to the hoard”.

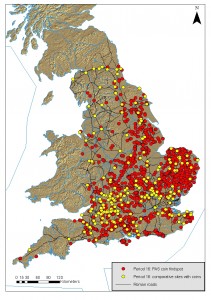

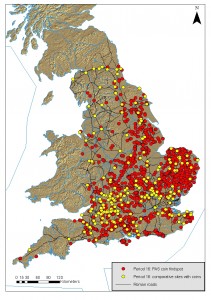

Locally: This is a significant group of coins and suggests some form of significant material wealth amongst the local populace. The archaeology of Shropshire is rich in Roman heritage but very little is known about the later periods. Generally it is thought that the early 4th century was a time of plenty with many of the troubles of the previous 50 years settled. In Shropshire though the later 4th century is poorly represented in excavated villas and large farmsteads as well as finds reported through the PAS. This is supported by the map of Roman coin loss reported through the PAS looking at coins made between 317-330 AD (created by Philippa Walton). This map shows the bias towards the South and East during this period.

PAS findspots of coins dated 317-330

Nationally: This hoard has given a unique opportunity to study a stratified deposit sealed within a pot. It is likely to give specialists further insight into other coin hoards without internal straigraphy which will add to our knowledge of the Romans.

What happens next and where will it go:

The hoard will be valued by Treasure Valuation Committee in London who will advise on the reward payable to finder and landowner.

Once a reward has been fixed, Shropshire Museums hope to raise funds to acquire the hoard for display within the county.

Peter will be speaking about recent PAS finds from Shropshire – including this important hoard – at an Archaeological Dayschool in Shrewsbury, Shropshire on 12th November 2011.

10/21/2011

Some of the Bredon Hill hoard

The discovery of the hoard – Richard Henry, FLO for Worcestershire and West Midlands

Richard Henry with some coins from the hoard

On the 18th June 2011 Jethro and Mark spent half an hour enjoying the view from Bredon Hill before picking up their detectors for the afternoon. Within five minutes of detecting they had found the site of the hoard. The initial signal only revealed an iron nail and after removing it the machine was placed back in the hole. Immediately the detector indicated there was a lot more metal at that spot.

After digging deeper large sherds of pottery were discovered before finding the first three coins. The detector registered “overload”. Neither detectorist wanted to get their hopes up but as coins continued to appear it was clear they had found a large coin hoard; both men were removing coins for the next two hours. The soil was then replaced along with the turf; from a distance the find spot was then barely visible.

The hoard was reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme on the 20th June. Within the hour the Finds Liaison Officer was with the finders and the landowner looking at the find spot, having a preliminary look at the coins and the vessel as well as discussing the possibility of an excavation with the landowner. First impressions of the hoard were that it in all likelihood numbered 5,000 – 10,000 coins and dated to the 3rd century.

The next day the local Archaeological Officer and Worcestershire Historic Environment and Archaeology Service were informed and in the afternoon, the Finds Liaison Officer, Tom Vaughan and Debs Fox went to the site to confirm an excavation would be undertaken at the start of July. A closer examination of the hoard was undertaken and some preliminary photographs were taken. They were mostly in good condition although in need of conservation, a process which would take time and money. As can be seen with the image of the radiate of Probus, most were already identifiable. The vessel in which the coins were deposited was a Severn Valley Ware storage jar dating to the same period.

At the start of July, archaeologists from WHEAS excavated a small trench centred on the find-spot. The aim of the excavation was to establish the archaeological context of the hoard. In particular, the team wanted to establish whether the hoard had been buried in open ground, like most hoards, or on a settlement of some kind, as suggested by the earlier finds, which included a Roman bow brooch. The team included both of the metal-detectorists who found the hoard, as well as the Finds Liaison Officer, David Kendrick and Debs Fox of Museums Worcestershire.

The hoard find spot excavations

The results suggest that the hoard was buried in the ruins of what had been a villa (in the modest, Romano-British, sense of the term). Villas expand and increase in number in the late 3rd century when in other areas of the Roman Empire provinces are suffering. The earliest features found in the trench were the stone foundations of half-timbered buildings. The first foundation was sealed by a deposit of soil and flat stones, interpreted as a surface. That deposit was sealed by another one. The artefacts (including one coin) found in these deposits date from the second century to the late third century.

The second foundation was cut through these deposits and sealed by soils containing earlier artefacts. Two postholes and two stake-holes were found at this level: they may represent a timber building. These features were sealed by a soil containing late third or fourth century pottery and two late third century coins. The latest man-made deposit was a layer of soil and rubble containing late 4th/early 5th century shell-tempered ware. The pit for the hoard was dug through this deposit or the soil that formed above it. The soil contained the latest coin found in the excavation – a copy of a House of Constantine nummus dating to c.355 – 361 AD.

The excavation took two weeks, the post-excavation, conservation and research will take years. It is surprising how long the process will actually take and how much it will cost but the hoard will be an important part of any research into Roman Worcestershire in the later Roman Empire. After the coins were deposited the first task we had to undertake was to separate the soil, naturally dry the coins and supply an initial count. This took long time as anyone who has had to count 3874 coins would understand! Over the next four hours the coins and the soil were painstakingly separated, ultimately the weight of the coins was over 11 kilograms with 3 kilograms of soil – and one centipede! The coins were initially sorted into the groups which would require conservation, including over 900 which were stuck together in clumps.

The coins were then securely secured and left to dry naturally before being collected by the Treasure Team at the British Museum in mid July to be cleaned and then identified so that a Coroner’s report could be written for the inquest.

Conservation and Identification

Richard Henry sorting coins

Throughout the whole process the condition of the coins was crucial. It was essential to clean the coins and separate them so that they could be stabilised, identified and their condition evaluated. Due to the size of the hoard on the 15th July a member of the Treasure team collected the hoard and took it to the British Museum.The coins were cleaned and dried by the Conservation Department at the British Museum. The coins required considerable attention so that the hoard could be used for research and preserved for future generations to admire. As can be seen in the images of a single coin of Florian on the day that they were reported and then after they had been cleaned.In September an “Emperor count” was undertaken so that a Coroner’s report could be written. This is an essential part of the process for the valuation of the hoard and the “Emperor count” was conducted by members of the Coins and Medals Department of the British Museum as well as the Finds Liaison Officer.

The “Emperor count” is perhaps simpler than would be imagined; each emperor was given a different tub. Correct identification was essential so this was a painstaking process. A full detailed list of the “Emperor count” will be discussed in detail in the booklet on the content of the hoard.

So what next?

The hoard is currently going through the treasure process, within the next few months the Coroner’s inquest will be help to decide if the hoard is legally treasure under the terms of the Treasure Act (1996) which is explained on this site under the Treasure section.

After the inquest has been held and it has been declared treasure it is the job of the Treasure Valuation committee to decide a fair market value for the coins so that the finders and landowner can be rewarded as well as giving Museums Worcestershire an opportunity to acquire the hoard.After the hoard has been valued the museum will have 4 months to raise the money so that they can acquire the hoard and preserve the find intact for future generations to admire and academic research.

Florian pre cleaning

Florian pre cleaning

Florian post cleaning

The Hoard’s contents

The Roman radiate was the main denomination of the 3rd century AD. It is described as a radiate because of the crown often associated with the sun god Sol. Theoretically the radiate was a double denarius but by the 250s the radiate was highly debased. The coins range from 244 to 282 covering a period of 38 years consisting of the coins of 16 different emperors and the wife of Gallienus. There are issues of emperors from the Central Empire and the Gallic Empire where seven rulers held power over Britain and Gaul between 260 and 274.

List of Emperors

Central Empire

- Philip II (244 – 247) 1

- Valerian I (253 – 260) 1

- Saloninus (258 – 260) 2

- Gallienus (253 – 268) 433

- Salonina (253 – 268) 48

- Claudius II (268 – 270) 352

- Divus Claudius (270) 77

- Quintillus (270) 23

- Aurelian (270 – 275) 17

- Tacitus (275 – 276) 15

- Florian (276) 3

- Probus (276 – 282) 36

Gallic Empire

- Postumus (260 – 269) 67

- Laelian (269) 7

- Marius (269) 9

- Victorinus (269 – 271) 817

- Divus Victorinus (271) 1

- Tetricus I (271 – 274) 1,159

- Tetricus II (272 – 274) 485

- Uncertain 212

- Copies 42

- Illegible 67

Total in hoard: 3,874

The Central Empire

The 3rd century was a period of turmoil, rebellions, invasions and civil wars where generals flexed their muscles in an attempt to gain power. The vast majority died a gruesome death at the hands of their opponents and held power for a short amount of time causing chronic financial instability. A period of what can be described as relative stability when considering the 3rd century arrived when Valerian gained control. He and his son Gallienus jointly ruled the empire until Valerian’s death in 260 AD fighting the Sassanian Persians. Valerian was defeated in battle at the head of legions severely depleted by plague. Valerian suffered a gruesome and humiliating death; the sources suggest that molten gold was poured down his throat before he was stuffed with straw.

After years of barely holding onto power, which included the Alamanni raiding Italy itself in 268 Gallienus was assassinated. Claudius II gained control and for two years the empire recovered. Claudius defeated the Goths, claiming the title Gothicus before dying of the plague, probably small pox, his natural death was a rare occurrence in this period. His brother Quintillus was declared emperor but his reign was short lived, lasting between 17 and 177 days depending on the source read.

In 274 Aurelian defeated Tetricus I reuniting the Empire. He rebuilt the walls around Rome and reformed the coinage creating a larger radiate with a higher silver content. Although not a popular ruler Aurelian was successful in contrast to the majority of his predecessors of the 3rd century and he earned the title Restorer of the World. Even so in 275 he was also murdered. His successor Tacitus was already over 70 when he became emperor, he defeated the Goths before dying of fever. His brother Florian became emperor before being defeated by Probus having ruled for only 88 days. Probus appears to have taken a real interest in Britain on which the 3rd century had a profound effect. In 277 he lifted restrictions on growing vines in the province and it became an important source of food and wine producer. It was the start of an agricultural boom. Probus also settled barbarians in Britain before he was assassinated (Three Roman coin hoards from Wiltshire terminating in coins of Probus (AD 276-82), Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine 102, pp. 150-9)

in 282.

The Gallic Empire

After the greusome death of his father Valerian Gallienus’ rule began to crumble. He left Postumus in control of Gaul and amid the chaos of invasions in 260 AD Postumus usurped power. A breakaway Empire emerged lasting for the next 14 years.In 260 Postumus usurped and proclaimed himself emperor building his power base around what is now known as Cologne. By 261 Gaul and Britain acknowledged him as Emperor. From the beginning Postumus made it clear he made no bid for power in Rome, his priority was Gaul. Ultimately this was his downfall, and the army were not happy with his decision not to march on Rome.

In 269 Laelian was proclaimed emperor.Laelian was easily defeated after Postumus captured Mainz and he was killed, his rule lasting barely lasting 4 months. Postumus was unable to control his own troops and they turned on him. After his death the Gallic Empire shrunk in size losing control of Britain. Marius was declared emperor after the death of Postumus, his rule lasting barely three months before he was killed by Victorinus. Victorinus was the Praetorian prefect. Victorinus’ rule lasted around 2 years when he constantly struggled to keep provinces within the Gallic Empire, in 271 he was murdered by a jealous husband.

In 271 the Gallic Empire was almost on its knees, power was seized by Tetricus I who made his son Tetricus II Caesar. Tetricus was a provincial governor in Gaul. As with Victorinus, Tetricus struggled to stop defections to the new Emperor Aurelian. He was decisively defeated by Aurelian in 274 when he abandoned his army and allowed them to be massacred. It is said that he was made a governor by Aurelian. In contrast to coins of the Central Empire issues of the Gallic Empire within the hoard are numerous, the most common being Tetricus I, Tetricus II and Victorinus. It was a period of high inflation and a heavily debased currency. This could also be linked to the fact that it is possible that under Tetricus and Victorinus around 5 – 6 million radiates were issued a week. This is a staggering number which was not equalled under the introduction of mechanical coin striking in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Examples from the Bredon Hill hoard

The hoard contains a number of interesting examples. After the death of Marius in 269 AD, Victorinus took control of the Gallic Empire. The early issues did not include the bust of Victorinus, perhaps this is because the mints did not know what their new emperor looked like. Instead they continued to use the bust of Marius with Victorinus’ full name inscribed on the obverse M PIAVVIONIVS VICTORINVS, interestingly a mosaic from Trier states his name as M.PIAONIVS.VICTORINVS.

In 268 Victorinus was co-consul with Postumus and the inscription states that he was tribune of the Praetorian guard, ironically this meant he was supposed to be the protector of the emperor. It appears that Victorinus could be regarded as a womaniser, as in 271 he was murdered by one of his officers whose wife he had tried to seduce. His mother arranged for his deification and Victorinus was declared a god, coins were issued celebrating this event.

A common theme throughout is debasement; coins which were meant to be around 90% silver contained barely 1%. It is interesting to see that under the reformed coinage the fact that each coin had a higher silver content was advertised. The marks PXXI at the bottom of the coin denote the mint and the silver content. It is a stark improvement; although it is still only 20 parts copper to 1 part silver (5%).

Coins in the Roman period were not just issued in the name of the ruling Emperor. There are examples throughout the whole of the Roman Empire of coins depicting and in the name of the Emperor’s wife or mother. There are 48 examples of this within the Bredon Hill hoard, all of one woman, Salonina. She was known as an Augusta and was the wife of the Roman Emperor Gallienus. Although in this period the Emperors were depicted with radiate crowns, females on coins were depicted with a lunar crescent behind the bust, as can be seen with this example.Each coin was struck by hand, consequently errors are common place unlike today when a major error by the mint becomes headline news, as can be seen with some 20ps missing a date from 2008. The most common error is coins being mis-struck, therefore having to be struck twice. Other errors can be seen within the hoard – there are examples where a coin is a hybrid of two types, such as this coin of Claudius II. Or where two bronze discs have been inserted before striking instead of one, the result being one coin with just the Emperors bust and a blank reverse, the other with just the reverse and a blank obverse.

09/12/2011

September 12th, 2011 by Angie Bolton

The CBA in the West Midlands is organising a dayschool entitled Recording your past, Enriching your future. It is

aimed at anyone researching archaeology or local history in the West Midlands and gives people the opportunity to gain

an understanding of Historic Environment Records / Site and Monuments Records in the West Midlands area.

The programme is as follows:

10.15am – Arrival, refreshments and welcome

10.45am – Historic Environment Records and how to use them:

Victoria Bryant, Worcestershire Historic Environment and

Archaeology Service

11.15am – Funding opportunities for local projects: Andrew Meredith,

A Meredith Associates

11.45am – Know Your Place – enabling people to explore their

neighbourhoods through historic maps, images and related

information: Peter Insole, Bristol City Archaeological Officer

12.15pm – Coventry Historic Environment Project – Volunteering in

Coventry: Eloise Marwick, Coventry Historic Landscape

Characterisation Officer

12.45pm – Lunch – NB. Lunch is not provided but please take the

opportunity to step out into Worcester’s historic High Street to

grab a sandwich.

During the lunch break there will be an exclusive opportunity to take a

tour of The Guildhall basement and cells, not normally open to the

public.

1.45pm – Project TBC

2.15pm – The Warwickshire Flickr Project: Christina Evans, Warwickshire

Historic Environment Record

2.45pm – TBC

3.15pm – Community Archaeology and the CBA: Dr Suzie Thomas,

Community Archaeology Support Officer, CBA

3.45pm – General discussion and questions

4.15pm – Historic Environment ‘Fayre’ – Browse the stands and find out

more about research opportunities and information in your area.

Archaeological services, local societies and local projects from

around the region will be represented, as well as a finds

identification session by the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

For more details and to download a registration form please follow link below:

http://www.britarch.ac.uk/cbawm/meetings.php#days

09/08/2011

Exhibition in East Sussex on the role of the Coroner

September 8th, 2011 by Ian Richardson

Television shows and movies, and sadly, real-life tragic events have familiarised the public with the concept of the coroner as the person who investigates sudden or mysterious deaths. Important as this is, it represents only one aspect of the coroner’s duties.

Coroners also play an important part in the administration of the Treasure Act 1996. The coroner is the body to whom finds of potential Treasure must be reported, and he or she decides -

a.) whether the find constitutes Treasure under the terms of the Treasure Act 1996

b.) who should be regarded as the finder or finders

c.) the nature of the find circumstances – specifically where and when the item(s) was found.

The Eastbourne Society (East Sussex) has organised a temporary exhibition at the Eastbourne Heritage Centre on the many roles of local magistrates, the coroner in particular. The exhibition ‘Crime, Punishment and Local Justice’, runs through 29 October 2011. Among other things it sheds light on the coroner’s place in the Treasure process and provides information about the various stages involved in inquests into items of Treasure, their valuation and acquistion by museums. More information on the exhibition and the Eastbourne Heritage Centre can be found here.

With upwards of 20 cases of potential Treasure reported every year since 2004 in East Sussex, the coroner’s office there has certainly been well occupied in fulfilling its duties in this respect.

The Heritage Centre is run mostly by volunteers, and looks a lovely place to visit if you have the opportunity.

An item from Eastbourne recently acquired by the British Museum

08/18/2011

August 18th, 2011 by Peter Reavill

Over the past five years or so I have worked closely with Jeremy Hall, retired photographer of the Royal Armouries, Tower of London. His recent death is a great sadness to all that knew him. Jeremy, and his wife Jane, were regular volunteers at Ludlow Museum Resource Centre, working specifically on the arms and armour collections as well as helping with many other projects. Jeremy was also the museums unofficial ‘official’ photographer.

At heart Jeremy had a deep passion for the history of his village and the Marches in general. It is hardly surprising then that I managed to persuade him to take photos of the artefacts and coins leant to me to record with the PAS. He was always able to get the very best from an object, usually one that I had already spent an hour or so trying to get right. He was a true master of his art, always happy to help.

When working Jeremy seemed to be able to command the light and make it do his bidding; he was able to bring out the most subtle detailing within his subject with what seemed like effortless skill (which only comes with decades of experience). His studio set up was often very ‘Heath Robinson’, sheets of glass balanced, tracing paper over the very hot lights to soften their harsh shadows (or set light to the building) and scrunched up silver foil to reflect light back onto the subject. Jeremy was uncomfortable being observed, however, he worked closely with interns, trainees and other volunteers explaining his methods and passing on some of his knowledge and skill.

Jeremy was a very modest man and completely unassuming; his photos from the Armouries as well as recent work for the PAS and Shropshire Museums will stand the test of time as iconic images from a master photographer. He would be highly embarrassed by the praise which is rightly his due.

Jeremy was a lovely, kind and peaceful man, great company and cheerful as well. His dry humour was often the tonic needed to lighten the mood. He was generous with his time and he will be sorely missed. I’m glad that I met and spent time with him. I am proud to call him a friend.

Rest in Peace.

A few of Jeremy’s photos

Stone Roman figurine

The Myddle Coin Hoard

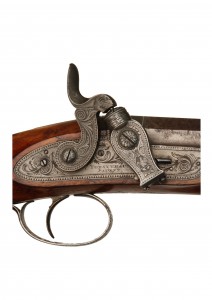

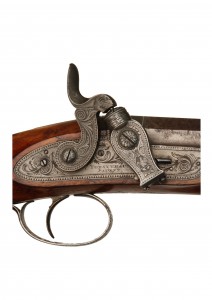

Lock Plate and Hammer on a musket in the Shropshire Museum Collection

West Shropshire Pendant, 7th century

The content contained within the Blog’s pages do not represent an official position from any of the organisations associated with the Portable Antiquities Scheme. They are solely those of the post’s author.

Florian pre cleaning

Florian pre cleaning