Total posts:

187

12/04/2012

Two new hoards of Treasure on show at the British Museum

Yesterday, 3 December 2012, saw the launch of the latest Portable Antiquities Scheme Annual Report (2011) and the Treasure Annual Report (2010) at the British Museum. Among the finds on display for guests to view were a selection of items from a hoard of Viking silver found near Bedale, North Yorkshire, and most of the coins from a hoard of Roman solidi found near St Albans, Hertfordshire. Both of these finds have now been put on temporary display in the British Museum for members of the public to enjoy while they go through the treasure administration procedure.

The hoard of Viking Silver material found in the Bedale Area on display in Room 2 of the British Museum

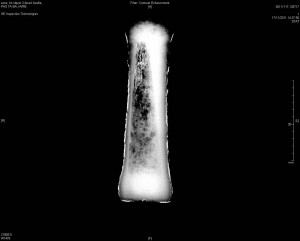

The hoard of Viking material is now in the Portable Antiquities and Treasure case in Room 2 (‘The Changing Museum’ gallery). On show is a large (546g) necklace composed of four strands of twisted silver wire, now corroded into position in the form of a sizable collar. This was not a discrete item of jewellery! The silver arm ring in the case appears to be well worn compared to similar examples from Silverdale, Lancashire hoard. The iron sword pommel is difficult to view with the naked eye because it is heavily encrusted in soil, but an X-ray by the British Museum’s Department of Conservation and Scientific Research has revealed the presence of elaborate gold-foil decoration. The case is filled out with a selection of some of the silver ingots (elongated masses of metal) found in the hoard.

The finders of the hoard, Stuart Campbell and Steve Creswell, attended the report launch and spoke to guests and the press about the find. When they initially located the hoard in May 2012, they only removed a few of the items before they realised what it was, and, following best-practice, they contacted their local Finds Liaison Officer (FLO) Becky Griffiths rather than attempting to remove any more of the hoard. Becky was able to organise a careful excavation of the hoard, which gave archaeologists the opportunity to record contextual information. As the hoard contains items that are over 300 years old and composed of over 10% precious metal, it was reported to the Coroner for North Yorkshire (Eastern District) as potential Treasure, under the Treasure Act 1996.

X-ray of the sword pommel from the Bedale Hoard

Yorkshire Museum hopes to acquire the find in due course. A report on the contents of the hoard has been prepared for the coroner by the British Museum, and the Coroner will hold an inquest to determine whether the find constitutes Treasure. We hope to have the hoard on display at the British Museum into the New Year.

The hoard of Roman gold solidi (coins) from the late 4th – early 5th century AD was found near St Albans, Hertfordshire, in September 2012. 141 of the 159 coins are currently in the British Museum (the remainder are currently still in the safe keeping of Verulamium Museum in St Albans). The coins have been put in the changing display in the Citi Money Gallery, and are accompanied by a short presentation on the discovery and identification of the coins. The coins from near St Albans represent one of the largest hoards of solidi ever found in Britain – the largest, from the Hoxne hoard, are in the collection of the British Museum.

As the hoard represents a find of two or more coins at least 300 years old containing more than 10% precious metal, it was also reported to the

Roman solidi from the hoard found near St Albans, Hertforshire, on display in the Citi Money Gallery at the British Museum

Coroner for Hertfordshire as potential Treasure. Verulamium Museum hopes to acquire the hoard, and a comprehensive report on the coins is being prepared for the Coroner, who will hold an inquest in due course to make a ruling as to whether or not the hoard fulfils the criteria for Treasure. It is anticipated that the coins will be on show at the British Museum for about a month’s time.

If the Coroners for North Yorkshire and Hertfordshire declare the respective hoards to be Treasure, they will vest in the Crown, which will seek to place them in the local museums mentioned above. The hoards will be valued by the independent Treasure Valuation Committee and the finders and owners of the land where the hoards were found will be eligible to receive a reward equal to the market value of the hoards.

11/29/2012

The Questions

Dave Crisp at the side of the trench

The quick thinking of metal detectorist David Crisp meant that the Frome hoard was not disturbed upon its initial discovery. This crucial action has allowed for a systematic study of the hoard beginning with its archaeological excavation. As the pot was excavated the ceramic sherds and coins were removed in layers. Each layer was carefully numbered and individually packaged. The British Museum received the hoard in around 60 bags, there being several bags from each layer of the pot. It was hoped that by excavating the hoard in layers it would reveal clues as to why and how the hoard was collected and deposited. These context layers formed a framework for organising the coins and retaining essential deposition information. Having reliable contextual information can help us answer questions like:

- Were all the coins put in the pot at the same time? Because the latest coins, of Carausius, are in the middle of the pot this does seem to be the case.

- Did the coins come from a variety of different individuals or sources? The answer seems to be yes because there are two distinct groups with coins of Carausius in them: a number of earlier Carausian coins were in the last group to be put in the hoard, at the top of the pot, while a large number of later Carausian coins were in a group in the middle of the pot.

- How many different groups (smaller pots, leather bags etc) were emptied into the hoard? We hope that by analysing all the coins, by layer and bag once they have been catalogued, we will gain an insight into how many different groups of coins were in the hoard.

Forward towards some answers

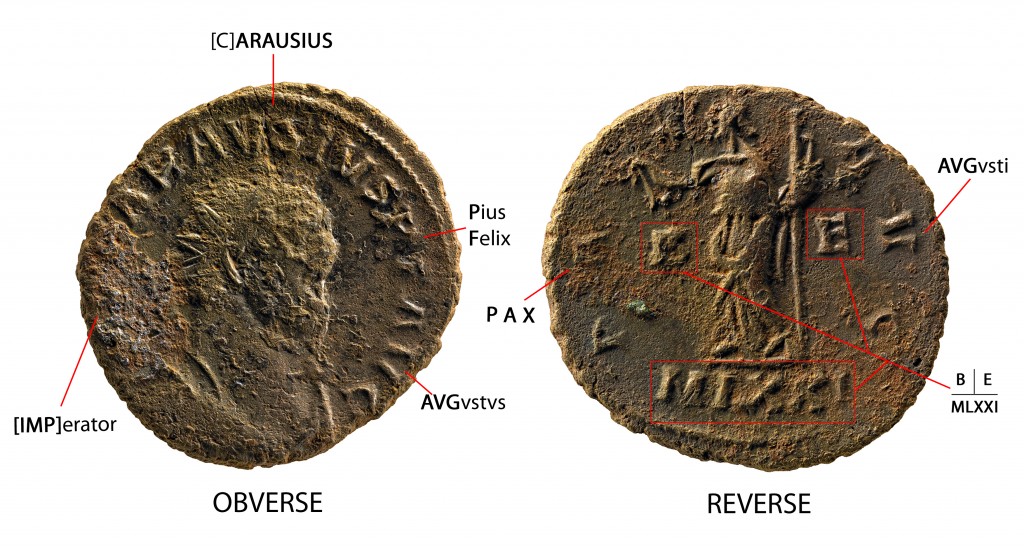

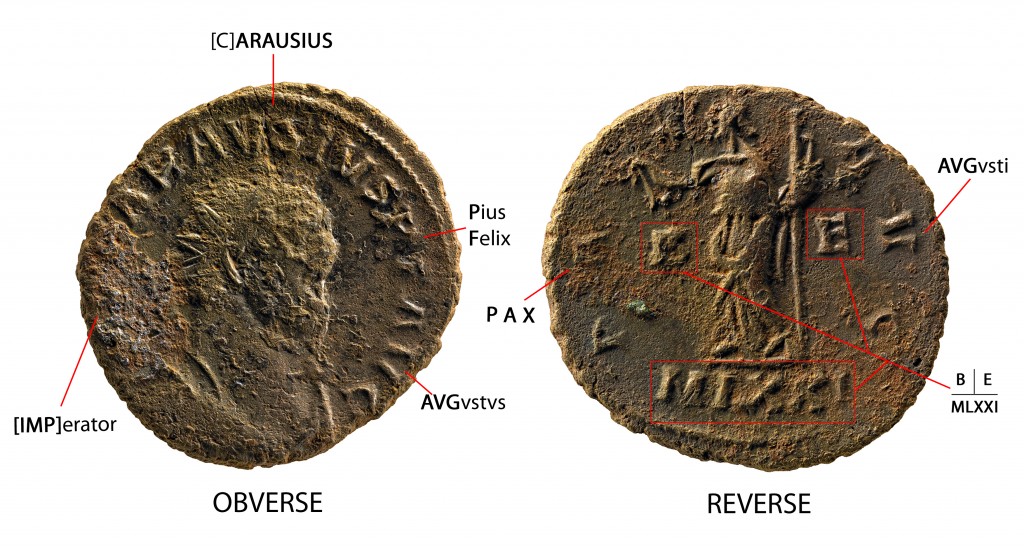

The information stamped onto the coins can help answer these sorts of questions. The LEGEND is the text on a coin which names the emperor (Augustus and Caesar in Latin) ruling at the time of issue. Other titles include commander (imperator), pious (pius) and blessed (felix). Because the Frome hoard was buried towards the end of period in which there were several civil wars and many barbarian invasions, there are around 25 rulers represented over a 40 year period (AD 253 to around 290) The mintmarks on the reverse of the coin often appear in the FIELDS and the EXERGUE of the coin, giving us important information about where and when a coin was struck.

In the illustration of a coin of Carausius (AD 286-93) below, the letters ‘B’ and ‘E’ are mint control letters in the field of the coin – we do not know what they stand for, but there was a large issue of coins bearing ‘B E’. The ‘MLXXI’ in the exergue stands for ‘Moneta Londiniensis’ (the mint of London), one part silver to twenty parts copper (i.e. 5% silver).

The mint marks are often recorded in the format shown at the bottom right of the image.

Carausius reigned from around AD 286 to 293, but we know that this coin was struck in the middle of his reign, around AD 290 and is one of the latest coins in the hoard.

Carausius set up a breakaway empire in Britain and Pax (the personification of peace, as seen on this coin) was the most common reverse type used on his coinage.

A conserved coin of Carausius

After their initial rinse in 2010, the coins were further sorted into bags by emperor, still depending on the layer they were from. Funds were then raised to conserve the approximately 30,000 coins needing further conservation, from the total of 52,503 pieces in the hoard. The relative rarity of Carausius’ coins made them our first conservation priority. The next priority was the illegible coins, pieces with so much corrosion that it was not possible to identify the emperor. These made up roughly 15% of the hoard. Finally, most of the remaining coins were partially identifiable with discernible emperor types but essential information on the reverse remained obscured. Coins in this condition were third in priority for conservation cleaning and have been selected by the curators.

The coin pictured above has been conserved to a legible standard, that is, all textual information has been sufficiently revealed that our numismatist colleagues can identify them. Notice the portrait of Carausius on the obverse still has his eyes and nose covered by corrosion as these areas are not a research priority. The ‘IMP’that precedes ‘CARAVSIVS’ remains hidden by the crystals of corrosion products. In this case, revealing the ‘IMP’ was not necessary as it is commonplace to find it preceding the name of the emperor and there is not much space for much else to fit there. However, there are instances where between the ‘IMP’ and the emperor’s name is a string of other letters that are shorthand for additional titles, such as ‘IMP C CARAVSIVS’ where the additional ‘C’ stands for ‘Caesar’. In other situations one finds ‘IMP C M CARAVSIVS’ where ‘C’ is again ‘Caesar’ and ‘M’ is for his given name ‘Mausaeus’. The presence of these additional letters implies that the coins were struck from different dies, which is important information for our investigations.

Carausius- (286-93): One of the five silver denarii from the Frome hoard after conservation, one of the finest specimens of its kind in existence

10/24/2012

Since the last post, the majority of coins from the Frome Hoard are still at their temporary home–The British Museum.

In 2010, a huge team effort allowed for the 52,503 coins to be cleaned of mud and clay by museum conservators and sorted

by Roman coin specialists.

Now, two years on from its discovery, the process to study and understand the hoard continues. The coins were handed to

two conservators–Ana Tam and Natalie Mitchell–for further work to reveal the fine details hidden beneath the corroded

surfaces. The next few posts will show what goes on when tens of thousands of coins require conservation.

Here’s an idea of what the coins looked like at the start:

Follow our weekly tweets and blog posts over the next couple of months to find out more! #FromeHoard or http://www.facebook.com/britishmuseum

10/05/2012

The Portable Antiquities Scheme joins Pelagios

NOTE: This has been recycled from: http://pelagios-project.blogspot.co.uk/2012/10/the-portable-antiquities-scheme-joins.html

Hacking Pelagios RDF in the ISAW library, June 2012

Earlier in 2012, the excellent Linked Ancient World Data Institute was held in New York at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW). During this symposium, Leif and Elton convinced many participants that they should contribute their data to the Pelagios project, and I was one of them.

I work for a project based at the British Museum called the Portable Antiquities Scheme which encourages members of the public within England and Wales to voluntarily record objects that they discover whilst pursuing their hobbies (such as metal-detecting or gardening). The centrepiece of this projects is a publicly accessible database which has been on-line in various guises for over 13 years and the latest version is now in the position to produce interoperable data much more easily than previously.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme database

Within the database that I have designed and built (using Zend Framework, jQuery, Solr and Twitter Bootstrap), we now hold records for over 812,000 objects, with a high proportion of these being Roman coin records (175,000+ at the time of writing, some with more than 1 coin per record). Many of these coins have mints attached (over 51,000 are available to all access levels on our database, with a further 30,000 or so held back due to our workflow model.) To align these mints with a Pleiades place identifier was straightforward due to the limited number of places that are involved, with the simple addition of columns to our database. Where possible, these mints have also been assigned identifiers from Nomisma, Geonames and Yahoo!’s WOEID system (although that might be on the way out with the recent BOSS news), however some mints I haven’t been able to assign – for instance ‘mint moving with Republican issuer‘ or ‘C‘ mint which has an unknown location.

Once these identifiers were assigned to the database, it allowed easy creation of RDF for use by the Pelagios project and it also facilitated use of their widgets to enhance our site further. To create the RDF for ingestion by Pelagios, our solr search index dumps XML via a cron job cUrl request, which is transformed by XSLT every Sunday night to our server and uses s3sync to send the dump to Amazon S3 (where we have incremental snapshots). These data grow at the rate of around 100 – 200 coins a week, depending on staff time, knowledge and whether the state of the coin allows one to attribute a mint (around 45% of the time.) The PAS database also has the facility for error reporting and commenting on records, so if you use the attributions provided through Pelagios and find a mistake, do tell us!

At some point in the future, I plan to try and match data extracted from natural language processing (using Yahoo geo tools and OpenCalais) against Pleiades identifiers and attempt to make more annotations available to researchers and Pelagios.

For example, this object WMID-3FE965, the Staffordshire Moorlands patera or trulla (shown below):

Has the following inscription with place names:

This is a list of four forts located at the western end of Hadrian’s Wall; Bowness (MAIS), Drumburgh (COGGABATA), Stanwix (UXELODUNUM) and Castlesteads (CAMMOGLANNA). it incorporates the name of an individual, AELIUS DRACO and a further place-name, RIGOREVALI. Which can further be given Pleiades identifiers as such:

- Bowness: 89239

- Drumburgh: 89151

- Stanwix: 967060430

- Castlesteads: 89133

Using Pleiades and Nomisma identifers allows the PAS database to enrich records further via the use of rdfa in view scripts and by the incorporation of the Pelagios widget and the ISAW javascript library on a variety of pages. For example, the screenshot below gives a view of a gold aureus of Nero recorded in the North East of England with the Pelagios widget activated:

The pelagios widget embedded on a coin record:

DUR-B4E094

The javascript library by Nick Rabinowitz and Sebastian Heath also allows for enriched web pages, this page for Nero shows the libary in action:

These emperor pages also pull in various resources from third party websites (such as Adrian Murdoch’s excellent talking head video biographies of Roman emperors), data from dbpedia, nomisma, viaf and the site’s internal search engine. The same approach is also used, but in a more pared down way for all other issuer periods on our website, for example: Cnut the Great.

Integrating Johan’s map tiles

Following on from Johan’s posting on the magnificent set of map tiles that he’s produced for the Pelagios project (and as seen in use over at the Pleiades site and OCRE), I’ve now integrated these into our mapping system. I’ve done it slightly differently to the examples that Johan gave; due to the volume of traffic that we serve up, it wasn’t fair to saddle the Pelagios team with extra bandwidth. Therefore, Johan provided zipped downloads of the map tiles and I store these on our server (if you’re a low traffic site, feel free to use our tile store):

Imperium map layer, with parish boundary. Zoom level 10.

The map zoom has been set to the level (10 for Great Britain) at which we decided site security was ensured for the discovery points (although Johan has made tiles available to level 11). This complements the other layers we use:

- Open Street Map

- terrain

- satellite

- soil map

- Stamen map watercolor

- Stamen map toner

- NLS historic OS maps

Each find spot is also reverse geocoded for a WOEID and Geonames identifier to be produced, elevation to obtained and subsequently we link to Aaron Straup Cope’s excellent woedb for further enhancement of place data. We also serve up boundaries derived from the Ordnance Survey Opendata BoundaryLine dataset, split from shapefiles and converted to KML by ogr2ogr scripts. The incorporation of this layer allows researchers (over 300 projects currently use our data) to interpret the results that they get from searches on our database against the road network and settlement data much more easily and has already gathered many positive comments from our staff and research colleagues.

By contributing to the Pelagios project, we hope that people will find our resources more easily and that we in turn can promote the efforts of all the fantastic projects that have been involved in this programme. What we’ve managed to implement from joining the Pelagios project already outweighs the time spent coding the changes to our system. If you run a database or website with ancient world references, you should join too!

09/07/2012

Most finds I deal with are returned to the landowner or finder after recording. Although interesting archaeologically, most are not of sufficient interest or quality for museum display.

SOM-ABAE0: Early medieval strap end

This late 9th or 10th century AD strap end of Thomas Class E type 4 from Mudford in South Somerset is a rare type. Class E strap ends are tongue shaped and larger than most strap ends of the period. On the continent and Scandinavia they were mostly used on baldrics (diagonal straps worn over the shoulder, often to hold a sword) and that was probably also the case in England. This particular sub-type has interlace decoration in a form known as Borre. Borre style was popular in Scandinavia from the late 9th century but less common in England. Borre decorated strap ends are mostly found down the east coast, in East Anglia or Lincolnshire. This item is therefore rare in general and also rare in the area so it is particularly pleasing that the finder has generously donated it to the Museum of Somerset where it is on temporary display.

Dr. Jane Kershaw has taken an interest in the strap end as part of her study on Viking style material found in England and blogged about it here. She has also drawn my attention to a good parallel from Wharram Percey. Full details of the parallels and the strap end can be found on the PAS record: SOM-9ABAE0.

06/14/2012

One of the sometimes frustrating things about this job is that because of the quantity of material to be recorded and because mostly the items belong to the landowners or finders and not the museum it is usually not possibly to do any detailed investigation or research in to them. I am aiming to make records which can then be used by other researchers rather than doing the research . It is therefore particularly pleasing when we get to go a little bit beyond the basic record.

Late Bronze Age Taunton-Hademarschen type axe

This axe (SOM-62A847) was brought in to me last year and was clearly an unusual type, much longer and thinner than most socketed axes. It is a variant of the Taunton-Hademarschen type with oval rather than square mouth dating to Late Bronze Age, 1000-800 BC. The name incidentally reflects the two ends of the known distribution and they tend to be concentrated from Somerset-South Wales, along the south coast and over to the continent.

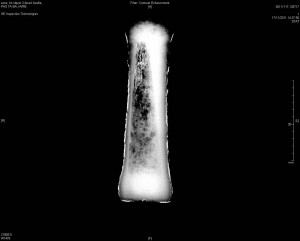

What struck me was the iron pan over the mouth of the socket. Iron pan usually builds up in waterlogged conditions and although the findspot it is now a dry ploughed field it was obviously wet in the past. Bronze Age metalwork is deposited into water so I speculated it may have been deposited into water originally and therefore the iron pan build up may have happen soon after deposition and could potentially preserve the haft.

We don’t have funding to X-ray interesting finds but my PAS colleague at the National Museum and Galleries Wales who is interested in Bronze Age material kindly stepped in and agreed to ask his conservation department to do it with some of his material. The result was very good.

As you can see there is a large chunk of the haft surviving, the x-ray clearly picks out the grain of the wood. They also checked the composition using non destructive XRF which showed it is the typical leaded bronze for this period with perhaps slightly less lead than is common. We have left the haft in situ for the moment as removing it may be a tricky job requiring a professional conservator and it maybe the shape is only preserved in the iron pan itself. The X-ray has confirmed its existence but also provides strong evidence the axe was originally deposited in a watery context.