Total posts:

187

09/07/2007

September 7th, 2007 by Philippa Walton

In two weeks time I will be leaving behind my role as a Finds Liaison Officer to start a Phd at UCL studying the huge number of Roman coins recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Having spent several years recording finds and coins, it will be nice to have the time to play around with the data and I hope that I will come up with some very interesting results.

As time goes by, I’ll post my latest results and rambling ideas! Roll on the 21st of September!

09/05/2007

Hello.

Herewith is notice of an archaeology conference coming up in October. The conference is looking at quarry sites. Big holes, lots of archaeology. Not sure how much it is, but you can get tickets from the bookshop at Jew Court, Steep Hill, Lincoln. The conference is at the university campus at Riseholme. Lovely deer park and ancient trees there – nice to look at if the speaker is dull.

Ads

ARCHAEOLOGY DAY CONFERENCE

Digging Big Holes – Archaeological Landscapes and Quarrying

Lincolnshire Aggregates Landscape Survey – Derek Carter

Lincolnshire Mining – Stewart Squires

Boxgrove - Mark Roberts

Langtoft - Alison Dickens

Baston - Andy Mudd

Saturday, 6 October 2007, 9.45 p.m. to 4.45 p.m.

At Lincoln University, Riseholme Campus

08/31/2007

Archaeology 2008 – A conference at the British Museum, 9th-10th February 2008:

A call for papers

A major new conference sponsored by Current Archaeology and the British Museum’s Department of Portable Antiquities and Treasure (Portable Antiquities Scheme) is being held at the British Museum on the weekend of 9th to 10th February 2008 to demonstrate the best current work being undertaken in British Archaeology. The conference will be divided into 20 minute slots. Lecturers will be expected to deliver a lively, informative and entertaining exposition of their work. Members of the Dept of Portable Antiquities and Treasure will be giving some lectures, but the organisers would love to have contributions from other members of the British Museum, especially those working overseas.

Please send your bids to conference@archaeology.co.uk, giving the title of the proposed talk, the speaker, and a summary (not exceeding 100 words) of the proposed presentation. If there are any queries, do not hesitate to contact Sam Moorhead (smoorhead@thebritishmuseum.ac.uk).

Sam Moorhead

Finds Adviser: Iron Age and Roman Coins

Dept of Portable Antiquities and Treasure

British Museum

London, WC1B 3DG

020 7323 8432

07/31/2007

Early this year, a metal detectorist called Tom Redmayne was searching in a muddy field in the parish of Fulstow in Lincolnshire. He had already found Roman pottery (Samian ware from Gaul), some late Roman coins and several lead weights. Then he found several pieces pieces of lead, two of which were folded over.When he carefully unfolded them, he saw that they had holes drilled in them. In the centre of each was an impression. He took them to Adam Daubney, the Portable Antiquities Scheme Finds Liaison Officer for Lincolnshire, who realised that they were coin impressions.

Adam brought the pieces down to the British Museum where he and I established that the impressions were caused by bronze coins of the Emperor Valens that had been hammered into the lead. The pieces were then folded over and the edges of the sheets pierced. This was probably so they could be hung up. So how do we interpret this?

In the reigns of the joint-emperors Valentinian I (364-75 AD) and Valens (364-78 AD), the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus tells us that a certain Valentinus:

who was a native of Valeria in Pannonia [Hungary], a proud man, had been exiled to Britain for a serious offence. Like some dangerous animal he could not stay quiet; he pushed ahead with his destructive, revolutionary plans nourishing an especial loathing for Theodosius [a general of Valentian and Valens sent to Britain].

The same scholar reports that this troublemaker Valentinus started a rebellion which was quashed. He then describes the catastrophic events in Britain, commonly called the “Great Barbarian Conspiracy”, when Saxons, Picts and Scots (from Ireland) all ravaged the Roman province. Britannia was saved only by the swift actions of General Theodosius.

Modern historians have tended to overlook the revolt of Valentinus. But it has been suggested that this was the catalyst for subsequent invasions, as the

barbarians sensed that Britain was in turmoil and therefore particularly vulnerable to attack. It might be that during the revolt of Valentinus, one of his

followers decided to curse the emperors. It was traditional to write curse messages on tablets which were rolled up or nailed to a temple wall (you can see Roman curse tablets from Uley in the Roman Britain Gallery; Room 49).

In the case of the find, it seems that instead of writing the emperor’s names, a coin with a picture of the emperor was used instead. Then the lead was folded over and the pieces possibly nailed to, or hung from, a wall.At a later date, the two pieces might have been ritually deposited, possibly in the ground. This is only my personal interpretation À“ we will never know for certain why they were made, but perhaps they were created by a follower of the rebellious Valentinus. Whatever the truth, we have not found other objects like these in Britain.

The curse tablet is recorded as database record LIN-57B091.

07/12/2007

Staff from the Portable Antiquities Scheme, the British Museum and dozens of metal detectorists have been working together to uncover the mystery of a long-lost cult to the Celtic god Totatis in Lincolnshire, dating to the late Iron Age and Roman period. For many years metal detectorists have been finding gold, silver and bronze Roman finger rings that all bear an enigmatic inscription containing three letters, reading ToT, and the majority of these come from Lincolnshire. Roman finger rings are sometimes inscribed with the name of a god who the wearer was devoted to, such as Mars, Minerva and Jupiter. The identity of the deity only known as ToT remained a mystery to scholars however, because there was no Roman or Celtic deity whose name began with the letters Tot, although scholars presumed that it was an mis-spelt abbreviation of the god Toutates, who was one of the principal deities of the Celtic world. Toutatus is known from a number of stone inscriptions in Britain and on the continent, and his name is often spelt in a variety of ways, including Teutates, Toutiorix and Teutanus. The rings are very Roman in style but contain a native inscription, which shows that the Romans were tolerant of native religion and allowed tribes to continue to worship them.

Adam Daubney, Lincolnshire Finds Liaison Officer for the Portable Antiquities Scheme has been keeping a close eye on the rings for a number of years, hoping that one day someone would find a ring with a complete inscription. Years of research and liaison with metal detectorists brought the number of rings known to fourty-four, including two elaborate gold examples, and very recently, one ring was eventually found by metal detectorist Greg Dyer which bore the inscription DEO TOTAT, confirming the deity as Totatis. The inscription translates as To the god Totat(is), and on one shoulder is the word “FELIX”, meaning “happy”. The other shoulder of the ring is missing, however there is a common Roman phrase “Vtere felix”, which basically means “use (this and be) happy”, and so the ring reads “To the God Totatis, use this and be happy”. Although it is unclear whether the ring is the object dedicated to the god, or whether it relates to the wearer of the ring, what is clear is that in the 2nd and 3rd century AD in Lincolnshire there was a strong tribal cult worshipping the deity, perhaps even attracting more followers than the traditional Roman gods such as Mars and Minerva.

There are very few ancient documents that mention Toutatis, however those that do paint a picture of a fearful warrior god who demanded human sacrifices. According to a document written in the 9th century, Worshippers of Toutatis used to plunge his victims headfirst into a vat of liquid until drowned.

What is furthermore fascinating about the rings is that their distribution highlights the tribal territory of the Iron Age tribe that existed at the time of the Roman conquest. The tribe known from inscriptions were called the Corieltauvi, and they covered the region east of the River Trent through Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire.

This evidence shows us that the native British population in the region were still acting and moving as a unified tribe well in to the Roman period. The old thought that the Romans invaded, conquered and ruled is now further under question based on this new evidence.

It seems that the cult died out with the Saxon invasions of the 5th century and was later replaced by Christianity, whose god recommended people love each other rather than plunge them headfirst into vats of liquid.

01/30/2007

Roman coins make up the single largest group of finds recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Because they are so common, and because they can be identified and dated quite easily, they make up one of the most important sources of evidence for Roman Britain.

Roman coins are used by archaeologists to help date sites and features in excavations. However, in the past, they have often discarded or ignored worn and supposedly illegible coins when better specimens have been found in the same context or layer. Historians use the inscriptions and designs on coins to cast more light on darker periods of British history, such as the decade when Carausius and then Allectus ruled a breakaway empire in Britain, AD286-96.

However, archaeologists and historians can also use coins to help reconstruct the nature of the Romano-British economy. For this study it is important to record the finds and distribution of all coins found. Two scholars, Richard Reece and John Casey, pioneered a new system for looking at site-finds (coins from excavations, field-walking and detecting) in the 1970s. They broke down the 400 years of Roman rule into different periods, in Reece’s case 21 as follows:

Reece Periods

| Period |

Date |

Period name |

| 1 |

pre-AD41 |

Pre-Claudian & Iron Age |

| 2 |

AD41-54 |

Claudian |

| 3 |

54-68 |

Neronian |

| 4 |

69-96 |

Flavian |

| 5 |

96-117 |

Trajanic |

| 6 |

117-138 |

Hadrianic |

| 7 |

138-161 |

Antonine I |

| 8 |

161-180 |

Antonine II |

| 9 |

180-193 |

Antonine III |

| 10 |

193-222 |

Severus to Elagabalus |

| 11 |

222-238 |

Later Severan |

| 12 |

238-260 |

Gordian III to Valerian |

| 13 |

260-275 |

Gallienus sole reign to Aurelian |

| 14 |

275-296 |

Tacitus to Allectus |

| 15 |

296-317 |

The Tetrarchy |

| 16 |

317-330 |

Constantinian I |

| 17 |

330-348 |

Constantinian II |

| 18 |

348-364 |

Constantinian III |

| 19 |

364-378 |

Valentinianic |

| 20 |

378-388 |

Theodosian I |

| 21 |

388-402 |

Theodosian II |

For every site, you then assign coins to the different periods which enables analysis of the site against other sites. This is normally done by working out a per mills figure (as percent, but out of 1000 to make the figures easier to deal with) for each period. Below I provide some examples:

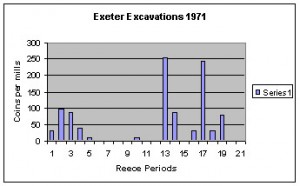

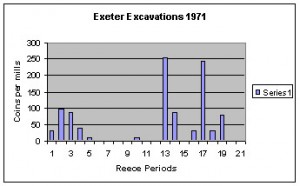

Fortress and Town: Exeter (Devon)

Coins from the excavations in the Roman fort and town of Exeter (1971). As for many early military sites, there are numerous coins from the 1st century AD. In common with some other urban sites, there is a fall in the number of coins after around AD 350.

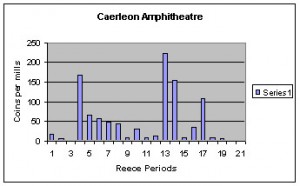

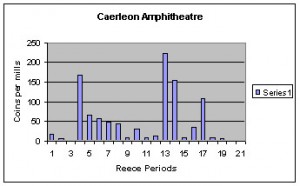

Fort: Caerleon Amphitheatre (South Wales)

Coins from the excavation of Caerleon Amphitheatre (1928). This chart shows a noticeable rise in the number of coins in period 4 (AD69-96), coins which were most common when the fortress was being built in stone. Like many military sites, there is a marked decline in the number of coins after around AD 350.

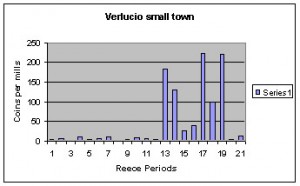

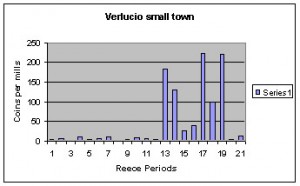

Small town: Verlucio (North Wiltshire)

Coins found at Verlucio small town, North Wiltshire (1970s-90s). These detector finds show that Verlucio was occupied throughout the Roman period. In common with other North Wiltshire sites, it has a very strong showing for the Valentinianic period (19: AD364-78), possibly reflecting the agricultural importance of the region to the late Roman authorities.

Villa: Chedworth (Gloucestershire)

Coins found at Chedworth Villa, Gloucestershire (before 1970). Like many villas, Chedworth’s coins mostly fall in the period after AD260 when British villas grew in number and size. Like North Wiltshire sites, Chedworth also has a strong showing for period 19 (AD364-78), again probably reflecting the agricultural importance of the region in the late Roman period.

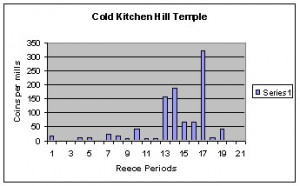

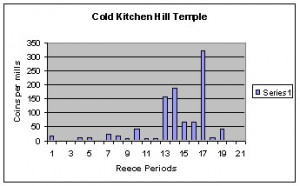

Temple: Cold Kitchen Hill (South Wiltshire)

Coins from the temple site at Cold Kitchen Hill, South Wiltshire (before 1929). This is an unusual West Country temple site because it has few coins after AD350. However, this dearth of coins does follow a trend shown at other South Wiltshire sites. None of these sites have any coins after AD378, a phenomenon shared by other nearby sites in Dorset and Hampshire.

These bar charts show patterns immediately. Forts and towns generally have earlier origins and so have more earlier coins (Exeter and Caerleon). Small towns, villas and temples are often founded later, or begin to flourish later, thus peaking in the 4th century (Verlucio and Chedworth). Obviously, there are numerous variations, some regional and some according to type of site. It is interesting that in Wiltshire, the sites in the northern part of the county tend to have more later coins than ones in the south – Verlucio has many more coins for periods 19-21 (AD364-402) than Cold Kitchen Hill, a site which has no coins after AD378. This suggests that sites closer to Cirencester were more prosperous in the late 4th century and/or went on using coins for longer. Patterns like these can be found across Britain giving us another insight into the fortunes of different parts of Britain in the Roman period.

What is important for this study is that all coins found are recorded. When I was working on coins from Wiltshire, I received about a 100 nice coins from a particular site for cataloguing. Having done them, I was given another 100 not so nice ones, but still easily identifiable. None of these coins were later than AD 378. I then asked for the rest to the surprise of the finder who wanted to know how I knew there were others. I said that I had not seen the grot. When I catalogued the grot, there were several coins from the period AD 378-402, thus changing the numismatic profile of the site significantly.

It is clear from my initial analysis of PAS coin records that detectorists are providing an enormous amount of new information about rural sites in Roman Britain, for example in Nottinghamshire. Some groups of coins are filling in large gaps in our knowledge, but for them to be reliable and valid for serious research all the coins from a particular site must be recorded. Recording all coins not only helps archaeologists and historians rewrite the history of Roman Britain, it can also bring unforeseen benefits to detectorists. One finder on the Isle of Wight, having been asked to bring in his grot for recording, was pleasantly surprised to find out that he had a Roman coin of Augustus that was so rare that there is not even a specimen in the British Museum.

So please everyone, note where you find your grot and make sure that it is shown to your Finds Liaison Officer. Together, we can help rewrite the history of Roman Britain.