October 29th, 2008 by Philippa Walton

I’ve just got back from the ICOMON* conference in Utrecht where I gave a short paper about the potential of the Portable Antiquities Scheme Roman coin data. Despite sudden nerves nearly getting the better of me when I stood up to talk and realised the assembled audience knew an awful lot about Roman coins, the paper seemed to go down ok – well, no one said what I was doing was a waste of time! It was all part of an interesting session exploring the different databases used to record site finds and hoard coins throughout Europe. Unsurprisingly, there are a quite lot of them, although none are as developed and as useful as the PAS database and not all are accessible online. At the moment, it would be a struggle to do similar research to mine in other European countries so I count myself rather lucky.

Other highlights of the conference included watching Euros being minted, hearing of another riverine Roman deposit (this time in Verona) which might be a good parallel for Piercebridge in County Durham and eating my way through 500 Euro chocolate bank notes..Yum.

*ICOMON = The International Committee for Money and Banking Museums

The new ICOMON website now holds my paper from their Vienna conference last year.

October 22, 2008 Sam Moorhead

The discovery of two gold coins sheds light on a little known British Emperor.

Two gold coins of the emperor Carausius have just been found on a construction site in the Midlands. They were reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme and archaeologists are investigating the find further. Gold coins of Carausius are extremely rare, until now only 23 being in existence. The last example found was in 1975 in Hampshire and it is quite possible that we will have to wait for over 30 years before another one sees the light of day.

PAS record number: DENO-651C91

Object type: Coin

Broadperiod: Roman

County of discovery: Derbyshire

Stable url: https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/203507

Carausius was a Menapian (from modern Belgium). In the AD 280s he was the commander of the Roman Fleet (Classis Britannica) that patrolled the English Channel and North Sea. The fleet was commanded from Boulogne and one of its major functions was to defend Britain and Gaul (France) from Saxon raiders. Carausius fell foul of the Roman emperors Diocletian and Maximian, supposedly because he allowed the Saxons to RAID and only intercepted them afterwards, keeping the stolen loot for himself! Rather than hand himself over, Carausius declared himself emperor of Northern Gaul and Britain and set up his own mini-empire.

PAS record number: DENO-64DAE1

Object type: Coin

Broadperiod: Roman

County of discovery: Derbyshire

Stable url: https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/203503

In this outrageous act of brigandage the escaping pirate [Carausius] first of all seized the fleet which had previously been protecting Gaul, and added a large number of ships which he built to the Roman pattern. He took over a legion, intercepted some detachments of provincial troops, press-ganged Gallic tradesmen into service, lured over with spoils from the provinces themselves numerous foreign forces,Video jugar a la ruleta “Aces and faces 50 play power poker” – “Aces and faces 50 play power poker” se diferencia de los juegos de Video Poker est’¡ndar, en que se juegan 50 manos de cartas al mismo tiempo. and trained them all under the direction of the ringleaders of this conspiracy for naval duties [Part of a speech given in honour of Constantius I, the emperor who finally retook Britain]

The first gold coin comes from Carausius’ mint at Rouen. Carausius only managed to maintain control of Northern Gaul for a few years and coins from Rouen are very rare. This is only the tenth gold coin recorded for the mint, but is from the same striking as three other known specimens. It shows the emperor shaking hands with Concordia with the inscription in harmony with the army. The second coin comes from the mint of London which struck many coins throughout Carausius’ reign. However, this is only the fifteenth gold coin recorded from London and it is a unique type. It shows Carausius wearing a helmet decorated with an animal design. The reverse trumpets ‘Imperial Peace’.

Carausius successfully defended Britain against the central empire, and even struck coins in the names of Diocletian and Maximianus to curry favour with them; however, he did not survive a coup d’etat by his finance minister, Allectus, who was to rule Britain from 293 to 296. The Roman emperor Constantius I finally retook Britain in 296, killing Allectus and bringing an end to Carausius’ breakaway realm.

Why these coins were buried we will never know. A Roman soldier might expect to earn twelve gold coins a year before deductions were made for his expenses. The wheat he needed to make bread for a year would have cost almost 2 gold coins. For one gold coin, someone could have bought almost 100 bottles of wine or about 50 litres of olive oil. However, ten gold coins would have been needed to buy a pound of white silk.

Below follows my actual write up of these coins and they were featured in today’s Times.

Both the coins were struck in the reign of Carausius (AD 286-93), one at the mint of London, the other the mint of Rouen. Gold coins of Carausius are extremely rare, these two specimens increasing the corpus of Huvelin from 23 to 25, 15 for London and 10 for Rouen.

- Gold Aureus (20mm; 4.65g; Die Axis 12)

London

Obv. VIRTVS CAR / AVSI; Ornately cuirassed and helmeted bust left (the helmet with an animal running left, possibly a ‘big cat’).Rev. PAX AVG; Pax standing left, holding branch in right hand and vertical sceptre in land.

Mintmark: -//-

This coin is unpublished. It is the third London aureus of Carausius to bear a helmeted bust. The earliest known example, now in the Bibliotheque Nationale, has the obverse legend VIRTVS CA-RAVSI and shows Carausius helmeted to the left, but holding a shield and spear (Huvelin no. 10). The Midlands coin is much closer to the second example which was acquired by B. A. Seaby in 1978, and was possibly found near Lille in France (Seaby Coin and Medal Bulletin No. 713, February 1978, pp. 36-7). This coin has an identical obverse legend (VIRTVS CAR-AVSI) and helmeted bust is also left facing, but is draped and cuirassed (Huvelin no. 11). Furthermore, there is only has a linear design on the helmet, there being no animal. In style the two pieces are similar, possibly both sunk by the same die engraver, but the Midlands example has a better modelled bust. Although Pax appears on the reverses of a number of Carausian gold coins (RIC V, nos. 3-5; Huvelin nos. 12-15), this is the first example with the legend PAX AVG and no mintmark or other exergue inscription. Given the common occurrence of this Pax type on bronze coins of Carausius, it might not be an unexpected type.

- Gold Aureus (19/21mm; 4.70g; Die Axis 6)

Rouen

Obv. IMP CARAVSIVS AVG; laureate, draped and cuirassed right.

Rev. CONCORDIA MILIT VM(in exergue); Emperor standing right, clasping the hand of Concordia

Reference: RIC 624; Huvelin 3-5

This coin has the same obverse and reverse dies as Huvelin nos. 3-5. Huvelin no. 3 is in the British Museum (4.54g) and is more worn. Huvelin no. 4 was originally described by William Stukeley in 1759 and is now in Berlin. Huvelin no. 5 was sold in the Evans Sale of 1934 (lot 1836) and its whereabouts is unknown. These coins also share the same obverse dies with Huvelin nos. 1-2 and the same reverse dies as Huvelin nos. 6-7.

References:

Huvelin H. Huvelin, Classement et chronologie du monnayage or de Carausius, Revue Numismatique VI Series, Vol. XXVII (1985), pp. 107-119.

RIC P. Webb, The Roman Imperial Coinage Vol. V, Part 2 (Spink, 1933)

October 10th, 2008 by Philippa Walton

I’ve come to the end of my year of data collection and have brought together more than 800 site coin profiles from England. It’s involved looking through more than 62 000Â Roman coin records on the database, scanning hundreds of excavation reports and reading every county journal published since 1990! I’ve just come accross a quote from Petronius’ Satyricon which I think sums up what I (and other applied numismatists) have been doing quite well.

…’They will pick even the smallest coins out of the muck-heap with their teeth’…

Now that combing through the muck is over, I need to do some work on what all those tiny coins mean. Statistics and Correspondence Analysis here I come!

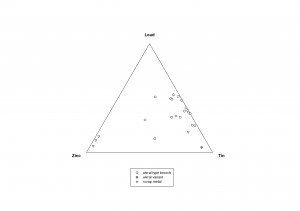

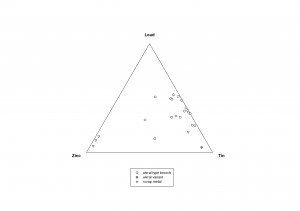

This is a very exciting week for me as Matthew Ponting has analysed the first set of brooch samples and so we now have some results. He has sampled 19 brooches so far along with 4 fragments of what we think are mis-cast brooches (and were hoping were mis-cast Wirral brooches!) using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy which allows the amount of each element in the alloy to be identified. The results so far are very encouraging for the project.

The aim of looking at the Wirral brooches more closely was to try and identify a possible location of manufacture through their distribution and the alloy composition analysis. What we hoped was that all the brooches would have the same alloy composition, suggesting that they were made in the same place or by the same person. Of the 19 brooches tested, 18 are similar enough to say they are all a leaded bronze and constitute a group. This is really good as it adds further weight to the thought that these were all made by one person/workshop (whether static or itinerant).

The one brooch which does not match is LVPL-059BC2. This has a very low lead content and cannot be said to be within the same group as the other 18. At first this could be a problem as it means not all the brooches are fitting the pattern. However Matthew and I then took the brooch out of the box and saw it was a variant! This was cause for many smiles and relieved sighs. Our idea is still on course. The only brooch so far with a different alloy composition is one which stylistically is not a typical Wirral brooch. The picture below shows that it shares some characeteristics with a typical Wirral brooch (stepped head, strong profile, small boss on the knee) but that it also has some different characteristics- mainly the bow decoration which is triangular as opposed to the usual linear panels.

The 4 waste fragments which were tested were a different composition again and so suggest that something completely different was being made on this site, not the Wirral brooches, even though Wirral brooches have been found in the same field as these waste pieces. Below is a diagram which Matthew created to show the results of the testing on one page with all 3 groups showing (typical Wirral, the variant and the 4 fragments). It is based on the formula Bayley and Butcher used when they tested the thousands of Roman brooches from Richborough and is a great way to easily and quickly be able to see groupings.

David Shotter is Roman coin expert based in Lancashire who keeps a catlogue of all Roman coins found in the North West of England has upturned the ID on LVPL-F139A5. He has corrected the ID from a quadrans to a copper alloy core of a dopy of a denarius of Antoninus Pius (138-161) minted in Rome, 145-161 AD.

This shows how tricky coins can be, especially when people in the past were so good at making copies. The forgers did such a good job of this coin that it was mistaken for a legal copy. It should have had a surface plating of silver to complete the coin and allow it to pass as a denarius but at a much lower cost to the makers. However, Sam Moorhead says

There is no evidence of any plating on the piece. It might be that it was never in fact plated’. This added to the confusion with the ID as usually plated copies will retain some of the plating, giving the clue as to their identity.

As mentioned previously, a large assemblage of coins from South Cheshire was put onto the database recently which added

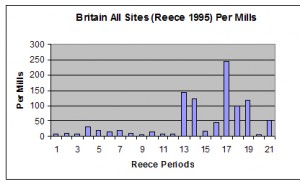

hugely to our data for this county. I have converted these coins into Reece periods to analyse them. The Roman period is

split into Reece periods for coins(see https://finds.org.uk/romancoins/reece.php

for more information). Using these periods and the formula Richard Reece devised, allows us to compare coin data from

different sites and areas. This is the type of work Philippa Walton is doing for the whole of England for her Phd which

is showing very interesting results already.

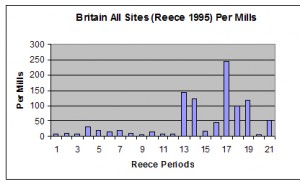

Reece looked at many sites across England and worked out an average site coin loss pattern. This is what he would expect

from a Roman site in England. Because of the way the formula works you can compare sites with different numbers of coins

as it is the percentage of each period which is the important thing. The Reece period data for the area in South Cheshire

seems to pretty well match Richard Reece’s British mean.

This was not expected as David Shotter has done a lot of work on the Roman coins in the North West of England and the

sites here do not match Reece’s norm. Sam Moorhead has suggested that the South Cheshire coins could have a different

pattern as the economy in that area was different to other parts of the North West. It is quite close to Shropshire which

has the sites of Wroxeter and Whitchurch (Roman Mediolanum) which have coin loss patterns more similar to Reece’s British

mean. it could mean therefore that people in this area were linked more to this area rather than Chester and other

Cheshire sites. This is very interesting as it shows that even within one county (Cheshire) there is variation in periods

of activity. It is a reminder that the boundaries we work with today are often meaningless when looking at past activity.

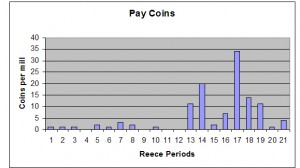

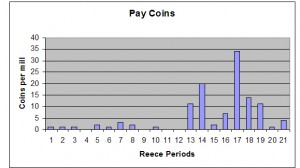

Below are the graphs which show the pattern of coin loss by Reece period, first from the South Cheshire data and second,

Reece’s British mean. The patterns can be compared and the similarities in the rise/fall of periods can be seen.