Roman coins make up the single largest group of finds recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Because they are so common, and because they can be identified and dated quite easily, they make up one of the most important sources of evidence for Roman Britain.

Roman coins are used by archaeologists to help date sites and features in excavations. However, in the past, they have often discarded or ignored worn and supposedly illegible coins when better specimens have been found in the same context or layer. Historians use the inscriptions and designs on coins to cast more light on darker periods of British history, such as the decade when Carausius and then Allectus ruled a breakaway empire in Britain, AD286-96.

However, archaeologists and historians can also use coins to help reconstruct the nature of the Romano-British economy. For this study it is important to record the finds and distribution of all coins found. Two scholars, Richard Reece and John Casey, pioneered a new system for looking at site-finds (coins from excavations, field-walking and detecting) in the 1970s. They broke down the 400 years of Roman rule into different periods, in Reece’s case 21 as follows:

Reece Periods

| Period | Date | Period name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | pre-AD41 | Pre-Claudian & Iron Age |

| 2 | AD41-54 | Claudian |

| 3 | 54-68 | Neronian |

| 4 | 69-96 | Flavian |

| 5 | 96-117 | Trajanic |

| 6 | 117-138 | Hadrianic |

| 7 | 138-161 | Antonine I |

| 8 | 161-180 | Antonine II |

| 9 | 180-193 | Antonine III |

| 10 | 193-222 | Severus to Elagabalus |

| 11 | 222-238 | Later Severan |

| 12 | 238-260 | Gordian III to Valerian |

| 13 | 260-275 | Gallienus sole reign to Aurelian |

| 14 | 275-296 | Tacitus to Allectus |

| 15 | 296-317 | The Tetrarchy |

| 16 | 317-330 | Constantinian I |

| 17 | 330-348 | Constantinian II |

| 18 | 348-364 | Constantinian III |

| 19 | 364-378 | Valentinianic |

| 20 | 378-388 | Theodosian I |

| 21 | 388-402 | Theodosian II |

For every site, you then assign coins to the different periods which enables analysis of the site against other sites. This is normally done by working out a per mills figure (as percent, but out of 1000 to make the figures easier to deal with) for each period. Below I provide some examples:

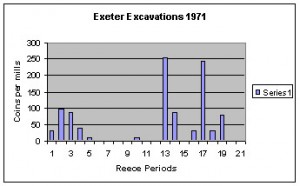

Fortress and Town: Exeter (Devon)

Coins from the excavations in the Roman fort and town of Exeter (1971). As for many early military sites, there are numerous coins from the 1st century AD. In common with some other urban sites, there is a fall in the number of coins after around AD 350.

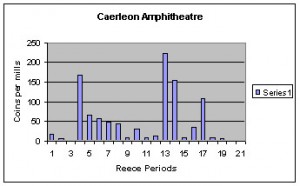

Fort: Caerleon Amphitheatre (South Wales)

Coins from the excavation of Caerleon Amphitheatre (1928). This chart shows a noticeable rise in the number of coins in period 4 (AD69-96), coins which were most common when the fortress was being built in stone. Like many military sites, there is a marked decline in the number of coins after around AD 350.

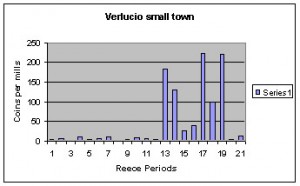

Small town: Verlucio (North Wiltshire)

Coins found at Verlucio small town, North Wiltshire (1970s-90s). These detector finds show that Verlucio was occupied throughout the Roman period. In common with other North Wiltshire sites, it has a very strong showing for the Valentinianic period (19: AD364-78), possibly reflecting the agricultural importance of the region to the late Roman authorities.

Villa: Chedworth (Gloucestershire)

Coins found at Chedworth Villa, Gloucestershire (before 1970). Like many villas, Chedworth’s coins mostly fall in the period after AD260 when British villas grew in number and size. Like North Wiltshire sites, Chedworth also has a strong showing for period 19 (AD364-78), again probably reflecting the agricultural importance of the region in the late Roman period.

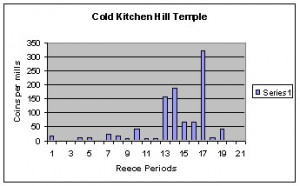

Temple: Cold Kitchen Hill (South Wiltshire)

Coins from the temple site at Cold Kitchen Hill, South Wiltshire (before 1929). This is an unusual West Country temple site because it has few coins after AD350. However, this dearth of coins does follow a trend shown at other South Wiltshire sites. None of these sites have any coins after AD378, a phenomenon shared by other nearby sites in Dorset and Hampshire.

These bar charts show patterns immediately. Forts and towns generally have earlier origins and so have more earlier coins (Exeter and Caerleon). Small towns, villas and temples are often founded later, or begin to flourish later, thus peaking in the 4th century (Verlucio and Chedworth). Obviously, there are numerous variations, some regional and some according to type of site. It is interesting that in Wiltshire, the sites in the northern part of the county tend to have more later coins than ones in the south – Verlucio has many more coins for periods 19-21 (AD364-402) than Cold Kitchen Hill, a site which has no coins after AD378. This suggests that sites closer to Cirencester were more prosperous in the late 4th century and/or went on using coins for longer. Patterns like these can be found across Britain giving us another insight into the fortunes of different parts of Britain in the Roman period.

What is important for this study is that all coins found are recorded. When I was working on coins from Wiltshire, I received about a 100 nice coins from a particular site for cataloguing. Having done them, I was given another 100 not so nice ones, but still easily identifiable. None of these coins were later than AD 378. I then asked for the rest to the surprise of the finder who wanted to know how I knew there were others. I said that I had not seen the grot. When I catalogued the grot, there were several coins from the period AD 378-402, thus changing the numismatic profile of the site significantly.

It is clear from my initial analysis of PAS coin records that detectorists are providing an enormous amount of new information about rural sites in Roman Britain, for example in Nottinghamshire. Some groups of coins are filling in large gaps in our knowledge, but for them to be reliable and valid for serious research all the coins from a particular site must be recorded. Recording all coins not only helps archaeologists and historians rewrite the history of Roman Britain, it can also bring unforeseen benefits to detectorists. One finder on the Isle of Wight, having been asked to bring in his grot for recording, was pleasantly surprised to find out that he had a Roman coin of Augustus that was so rare that there is not even a specimen in the British Museum.

So please everyone, note where you find your grot and make sure that it is shown to your Finds Liaison Officer. Together, we can help rewrite the history of Roman Britain.